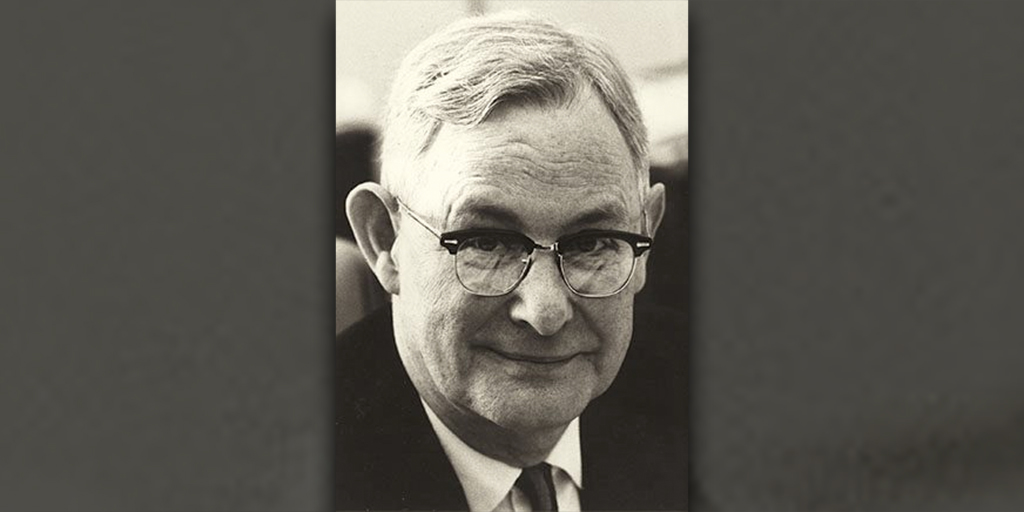

Dr. H. Bentley Glass: Ground-breaking geneticist — and Baylor grad

Have you ever heard someone say that cockroaches could survive a nuclear war? The idea is common enough today that even the Mythbusters have looked into it — and it’s an idea first noted by a Baylor grad. Dr. H. Bentley Glass, BA ’26, MA ’29, made that observation while studying the effects of radiation in the 1950s, and famous as it is, it’s just one aspect of Glass’ long and influential career as a scientist.

In fact, there was a time when Glass was one of the country’s most famous scientists. A professor of genetics at Johns Hopkins University, his name frequently came up in conjunction with new discoveries and scientific frontiers in the 1950s and 1960s, and his insights about the future of genetics (and, of equal importance, the ethics of genetics) captured the public’s imagination.

Born in China to missionary parents, Glass spent most of his childhood serving the people of eastern China before moving to Texas for college. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology from Baylor before earning his doctorate at UT. After his postgraduate work, Glass moved to Germany to conduct genetics research, where he witnessed (and was repulsed by) the early stages of Nazi influence on German life. He soon moved back to the U.S., eventually settling in Maryland for the bulk of his working life.

At Johns Hopkins, Glass helped shape the growing field of genetics. Some of his research on genetic traits led him to argue against race-based segregation and racial supremacy. He also studied nuclear testing and the impact of radiation on human genetics (leading to his revelation that cockroaches were best suited to survive nuclear war). His national profile grew as he served on the Atomic Energy Commission, authored regular newspaper columns, and served one year as editor of the respected journal Science.

Glass also grew to champion individual and academic freedom, having seen how his Jewish colleagues in Germany were treated. He eventually served as president of the Maryland chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and on the Baltimore Board of School Commissioners, where he oversaw desegregation.

As he saw where genetics was headed, Glass frequently discussed the ethics of such work. He was among the first to raise questions about how society would deal with the abilities to test for birth defects and create life in test tubes and laboratory settings — questions we still wrestle with today.

“As we become increasingly aware of the ethical problems raised by science and technology,” he said before his death in 2005 at age 98, ”the frontiers between the biological and social sciences are clearly of critical importance.” [Read The New York Times‘ obituary for Glass here.]

Sic ’em, H. Bentley Glass!