Juneteenth memories from Baylor’s oral history archives

Since 1970, Baylor’s Institute for Oral History has been preserving the memories of history’s eyewitnesses. Today, the archives include more than 7,000 interviews and more than 200,000 pages of transcripts — many of which have been digitized and made available in audio and/or transcript form online.

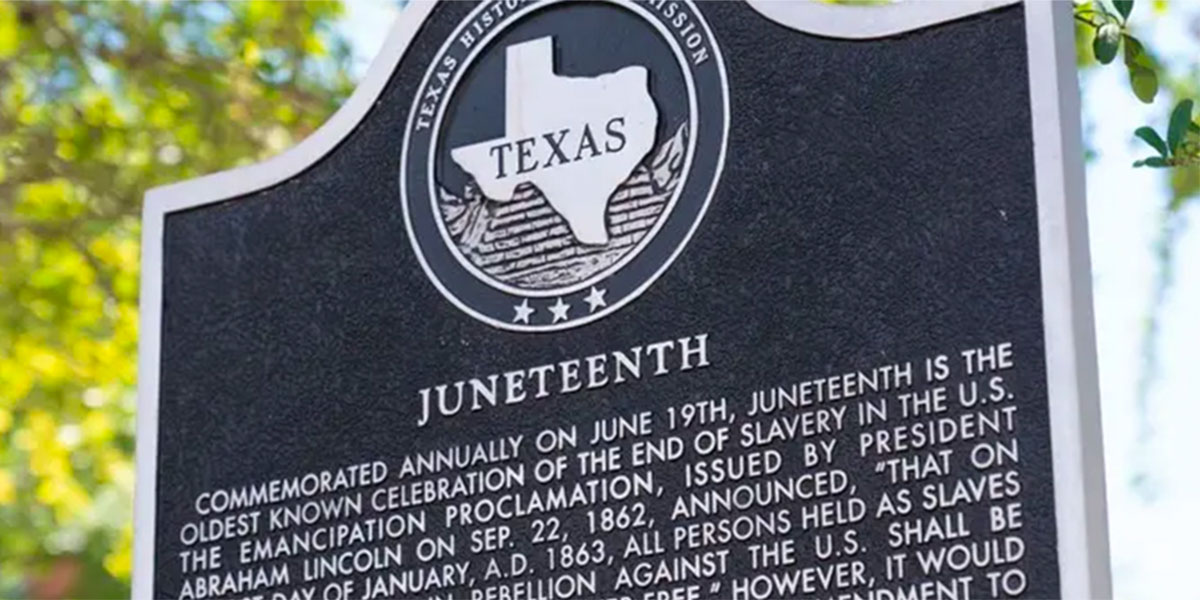

Among the collection are interviews with Texans from various eras who share their memories of Juneteenth — from June 19, 1865, when enslaved Black Americans in Texas first received news of their emancipation, to celebrations of that anniversary over the years.

Below are two examples from those interviews (edited here for clarity) — just a taste of the history to be found in the Institute’s archives:

Dr. Rowena Weatherly Keatts grew up in Lincolnville, Texas, an African-American community near Gatesville established by former enslaved persons shortly after the Civil War. The daughter of a former enslaved person, Keatts taught school in Lincolnville and later served as head librarian at Paul Quinn College in Waco. Her interview was conducted in multiple sittings in 1986 and 1987. (Click here for audio of the full interview.)

“My father’s name was Gus Weatherly. He was born in Centerville, Tennessee. His father had a plantation there. [His father] was white, of course, and he was the high sheriff there.

“My father was brought to Texas in a wagon with his mother. Mr. Weatherly had a daughter who married this man that was from Texas, and my father and his mother were given to this daughter as a wedding present. He brought them out here in a covered wagon.

“I don’t know the exact date that [my father] was born, but it was in the late 1830s or 1840s, because he was 18 years old at the close of the Civil War. He was the one of the persons that had marched — after they had found that he was free, he carried the flag in the parade that they had when they found out they were free. He [remembered] how they rejoiced, and he was one that carried the flag. They had a parade. They were just so glad, you know, and shouting… They were all just rejoicing about this freedom. Because he said this came to them, somebody came to Galveston on a boat. It spread, you know how news will spread, and that it just went from Galveston on around, around, all around, everywhere. And it finally reached out there, but that’s why — where the Nineteenth of June came, Juneteenth, they call it. That’s why — how it originated, because that’s the day that they found out that they were free.”

Linda Jann Lewis, a Waco native and former elections commissioner for McLennan County, was interviewed about her life in 1993. She recalls celebrating Juneteenth and learning the history firsthand as a child. (Click here for audio of the full interview.)

“The Giddings side of the family, my father’s side of the family — at the end of slavery, they were all at the Stroud plantation. That branch of the Giddings moved over to Robinson County and bought some land. So there is land in Robinson County today that is still in my family, that’s been there since the end of slavery, since Juneteenth, 1865, and the members of the family still own and control it. The Giddings bought several hundred acres; I think originally, it was a little over three hundred acres. The family story is that the great-great-great-grandfather and his sons cut wood, corded wood, and sold wood for 25 cents a cord, and bought the property.

“My grandmother had some friends her age and a little older. There was one woman, Nancy Hagworth, who also came from the Stroud plantation, and she was a distant relative because we were related — you know, all people came from the plantation. We called her ‘Sis.’ The thing about Sis, Mrs. Hagworth, was that she was six years old when slavery ended, and she remembered things. She used to tell me slavery stories. Her mother was the cook in the big house at the Stroud plantation.

“When the blacks at the Stroud plantation were freed, they dedicated a park there in Mexia — Emancipation Park, which was later renamed Booker T. Washington Park. The people who were freed there vowed that every year afterwards they and their descendants would come back and celebrate their freedom there. I remember a lot of times we went to Mexia on Juneteenth — actually, it was a whole weekend or week up to that. We would go and at a young age we would be introduced to relatives. There would be these ancient people, you know, really, really old, and you’d have to go up to them. My grandmother would say, ‘This is my son’s daughter,’ and ‘This is your cousin so-and-so through so-and-so.’ As a child, you really don’t know, but you hear the names. So I was aware of some of the names. What it did for me was to give me a sense of time and place. I knew that I came from some people who could accomplish some things through some horrible circumstances. It was like a reunion. A giant reunion of everybody who had descended from the Stroud plantation.”

Such stories are a reminder that what can seem like ancient history really wasn’t all that long ago.

The Institute for Oral History has exponentially more stories to share beyond these two brief examples. That begins with their online archives, and continues with the Waco History website, app and podcast — a joint effort with Baylor’s Texas Collection that features almost 200 stories, over 1,000 historic images, and hundreds of oral history excerpts. Dive in at baylor.edu/oralhistory and wacohistory.org.

Sic ’em, Juneteenth!